|

|

| Operating Systems Development Series | |

|

This series is intended to demonstrate and teach operating system development from the ground up. IntroductionWelcome! Yey, this is going to be a long one. This chapter is going to cover an advanced topic - the PE executable file format. We will be looking at covering PE resources, dynamic linking, and more. This chapter is also planned for an update to include more information to make the information as complete as possible. Most of what is included in this chapter is for information purposes only and are only included both for completness and in case any of our readers would like to provide support for them. Also please note that a lot of the information provided can also be found in the official PE specification. After this chapter, we will have everything we need to develop a loader and support a single tasking environment. Lets get started! File FormatAbstractThe Portable Executable (PE) file format is the standard executable file format used in several operating systems, including Windows and Windows-like OSs, such as ReactOS. It is also the standard file format used with booting on Extensable Firmware Interface (EFI) machines. The PE executable file format is a complex format, supporting relocations, symbol tables, resources, dynamic binding, and more. TermsVA (Virtual Address)A Virtual Address (VA) is a linear address in the Virtual Address Space (VAS) of the current program. All addresses in the PE executable format are virtual addresses. These addresses are 32 bit linear addresses. RVA (Relative Virtual Address)A Relative Virtual Address (RVA) is a VA that is relative to the base address of the executable program. The PE executable format uses RVAs in a lot of areas, so it is important to know what RVAs are and how to obtain linear addresses from them. RVAs are just offsets from the base address, thats all. So to obtain its linear address, just add the RVA to the base:

This one is important as we will need to perform this calculation in a lot of areas when parsing. Sections and the Section TableSections Advanced executable file formats typically use program sections to simplify the linking process and provide structure to the software. Sections simplifies the linking process by providing a standard method for instructions and data to be stored within the executable image or object file. A section typically has a name associated with what elements are inside of the section. For example, .data is a common section name that contains variable, uninitialized data. Other section names have historical backgrounds. For example, .text is a typical name of a section containing executable or object code. .bss is typically used for global, program-wide initialized data. Using the C++ toolchain, for an example, variables defined in the global namespace or as static are stored in .bss. The resulting bytecode generated after compilation is stored in .text. The PE executable file format typically includes one or more of the following section names:

Section Table Program files and object files contain multiple sections. The base location of each section, and the name of that section, is typically stored in a section table. In some implimentations, a section table can be a simple linked list of structures or a hash table - different implimentations exist. Symbols and the Symbol TableSymbols While programming in C++, you most likley have encountered the unfamous Undefined symbol linker errors (or in some implimentations of C, warnings. Thats right, fully compiling and linking without error *ahem* old MSVC). This happens do to calling a function or referencing a variable by name whose definition could not be resolved during the linking stage. Functions and variables are referred to as symbols by the linker. A symbol contains the name, and information about what it is: such as a data type and value, for example. During compiling, the compilier must keep track of these symbols to insure that the final program can be linked. If a symbol is used that is not defined in the current translation unit, but is an EXTERN symbol, the compilier will need to mark it as an EXTERN symbol when writing the symbols to the object file. If, during the linking stage, a symbol marked EXTERN still has no value associated with it (the symbol has no definition), the linker issues the above error. Symbols are what allows programmers to define variables or functions across modules, translation units, or libraries. There can only be one symbol with the same name through the entire program, and any libraries that it links with. Because of this, and the high probability of naming collisions with the use of high level languages, variable and function names typically have name mangling applied. This, of course, does not apply to assembly language. The name mangling applied depends on multiple factors, and differ between toolchains. Lets take a look. Here are some C function declarations, and their mangled symbolic name on the right. The number in the mangled name is the number of bytes for the paramaters.

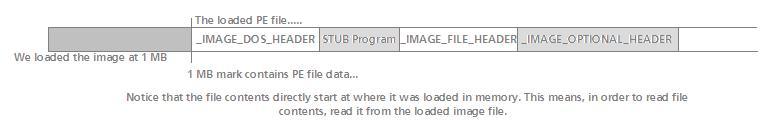

Notice that functions with the _cdecl call convention only have an underscore prepended. This allows C functions to be easily defined using assembly language, and allows C code to easily call those functions. There isnt any standard for C++ name mangling. Some compiliers might produce a symbolic name like ?h@@YAXH@Z, while others can produce __7h__Fi or W?h$n(i)v for the same function of void h(int). This makes it impractical to use with assembly language. It is still possible, however. Symbol table Simular to the section table there exists a symbol table. The symbol table allows a way for the software to look up symbolic names and information about the symbol, such as if its an exported symbol, its data type, properties, etc. Symbol tables are typically a linked list of information or implimented in hash tables. StructureAbstractWe have taken a look at the structure of the PE executable format in our MSVC++ chapter. When we load a PE executable in memory, that memory would contain an exact copy of our loaded file. This means the first byte within the first structure of the PE file format is actually located at the first byte from where the file was loaded in memory. For example, if we load a PE file to 1MB, the in-memory footprint might look like this:  The above image should look famailier to our readers who have read the MSVC chapter. Looking at the above image, if the PE file was loaded to 1MB, then the first on-disk structure, IMAGE_DOS_HEADER, begins at that location in memory, followed by the rest of the structures in the file (including padding). The above image is also an oversimplification - it does not, by any means, show the complete PE file format. The structure of the PE file format is fairly large, composed of a lot of structures and tables. Here is the complete format:

The above table lists the complete file format - from beginning to end. Items marked important are required to know how to parse in order to just execute the program. All of the other information if provided for information purposes only. The only important members in IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER structure are the member that contains the address of the entry point, and image base address. We will cover parsing each section of this file in detail in the upcoming sections. We will also introduce the other structures used when parsing tables and directories as well. IMAGE_DOS_HEADER structureIMAGE_DOS_HEADER is the first structure of the PE file. It contains global information about the program file and how to load it. Most of the information contained in this structure were more relivant to DOS software, and are only supported for backward compatability. The structure follows the format:

Alright, a lot of interesting things in this structure. The initial CS:IP and initial SS:SP members should be ignored as the operating system normally allocates a stack space and code descriptor value for CS. These members were more prominent during the DOS area and software requiring v8086 mode. STUB ProgramOkay then! Lets look back up at the PE file image structure again (The above picture.) Notice how a DOS stub program is right after the IMAGE_DOS_HEADER structure. This is a useful program, actually. This is the program that displays "This program cannot be run in DOS Mode", if you try to execute a Windows program from within DOS. We can change the stub program by using the /STUB linker option:

When DOS attempts to load the executable, it will parse the IMAGE_DOS_HEADER structure and attempt to execute the DOS stub program because it is a valid DOS program. When running under the Win32 subsystem, the Windows loader will ignore the stub program. IMAGE_NT_HEADERSFollowing the STUB program is a structure, IMAGE_NT_HEADERS that contains the format of the PE header structures. Here is the structure:

The signiture must match with "PE\0\0", where \0\0 are null characaters. The IMAGE_FILE_HEADER contains additional information used by the loader and the complete size of the IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER structure. The IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER is the largest and most important structure in the file. It also does not have a defined size. In order to locate this structure, the OS loader must use the e_lfanew member of IMAGE_DOS_HEADER. e_lfanew is an RVA to this structure in memory, so in order to locate this structure, the loader needs to perform the following:

This assumes imageBase referres to the location where the program file was loaded into memory. Because older operating systems, such as DOS are not aware of this member of the header, it will be ignored by these OSs. This structure contains the format for the other two header structures. Lets look at the first of these structures. IMAGE_FILE_HEADERThe IMAGE_FILE_HEADER is the Common Object File Format (COFF) header structure. It follows the following format:

This structure isnt too complex. Most of the above is only useful for debuggers (symbol table parsing). SizeOfOptionalHeader is important - because IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER does not have a defined size, this member lets you know the size of the structure. Machine can be one of the following values:

In the usual case, it should be 0x014c as we are developing for the x86 architecture. Characteristics is composed of bit flags that can be bitwise-ORd by the linker to let the loader know different properties of the type of executable image this is. Heres the format:

The Windows headers use defined constants, such as IMAGE_FILE_RELOCS_STRIPPED and IMAGE_FILE_EXECUTABLE_IMAGE that can be used when setting these flags. As you can see, most of this structure is for information only for the loader on how to load the image. But wait! What about resources, symbol tables, debug info ... where is this at? Ah, behold the reason why IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADER does not have a defined size. Lets take a look! IMAGE_OPTIONAL_HEADERUgh, here we go. This is the most complex structure in the file. The good news is that you probably have seen this structure before:

First, take a look at that last member, DataDirectory. The constant, IMAGE_NUMBEROF_DIRECTORY_ENTRIES can, and has, changed through the years. This is that member that could change the size of this structure. We will look closer at that member a little later though as thats where all the fun stuff is at. You might be interested in why this is called an "optional" header even though its clearly not optional. This is due to it being optional for COFF object files. While its not optional for executable images, it is for object files :) magic can be one of the following:

A lot of the members in this structure really arent that complex. The subsystem member is Windows-specific. It tells Windows what subsystem the program requires in order to execute properly. It can be one of the following values (posted here for completness only)

The DllCharacteristics member contains bit flags that gives the loader information about the DLL. It follows the following format:

AddressOfEntryPoint is an important one. This member contains the RVA of the entry point function of the image (for DLLs this can be null as DLLs dont need entry points.) This is what our bootloader uses to call our entry point function in our kernel. Thats about all there is to it. You might be interested in what those other members are - for .text, .data, .bss etc. There is also that nasty looking DataDirectory member that we havnt looked at. We will look at those members closly later on. For now, lets look at executing a program! Executing a programAt this stage, if all that you would like to do is execute a program, all of the information has been provided. After loading a program, all that the loader needs to do is locate the AddressOfEntryPoint member from the optional header, and call that address. Remember that this is an RVA, meaning the loader needs to add this address to the ImageBase to obtain the linear address to the entry point function. Here is an example:

Thats all that is needed to execute a PE executable :) Data DirectoriesAbstractResources, symbol tables, debugging information, import, export tables etc are accessable from that nifty DataDirectory member of the optional header. This member is an array of IMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY's that can be used to access other structures containing this information. IMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY has the format:

Remember that DataDirectory is an array of IMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY's. Each entry in this array allows us to access the different data that we want to access. Here are the index entries:

For example, if you need to read the export table, reference DataDirectory[0]. If you want to read a resource, reference DataDirectory[2].VirtualAddress: Each of these sections contains their own structures that are required to parse the specific data. Lets take a look at some of the more useful ones. Reading the export tableThe export table contains all functions exported from libraries or DLLs, including their function addresses within that DLL, their names, and ordinal number. The Win32 API function GetProcAddress() works by parsing the modules export table by ordinal number or name and returning the address from it. This is one way reading the export table can be useful. To parse the export table, you need to first get the export directory structure. This is done by getting DataDirectory[0].

Remember that VirtualAddress in the IMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY structure is an RVA, so must be added to the image base. Now exportDirectory points to this nice structure:

This one is an easy one. AddressOfFunctions is an RVA that points to an array of function addresses. The function addresses, however are also RVAs. AddressOfNames is a pointer to a list of function names. All of these addresses are RVAs however so must be added to the image base in order to properly obtain the function name and address. AddressOfNameOrdinal is an RVA to a list of ordinals. The ordinals, being just numbers representing the exported functions and not addresses, arent RVAs. To properly parse the export table must be done in a loop. For example:

This can be used to impliment GetProcAddress() which can be useful in supporting DLLs. Reading the import tableSo... reading the export table wasnt hard enough, huh? Reading the import table isnt too hard, but is a little more involved then the export table. Ok, ok, whats the use for reading the import table? Its not so much the reading, but the writing. By writing entries into a programs inport table, you can allow function calls across libraries and DLLs without the need of a GetProcAddress() call. Windows performs this with delayed loaded DLLs and system DLLs. In order to read the import table, you need to locate the import directory structure. This is at DataDirectory[1]:

It is important to note that importDirectory points to an array of descriptor entries. Each of these entries represents a module that was imported, such as an import DLL. Lets take a look at this structure:

Its important to note that Name, OriginalFirstThunk and FirstThunk are RVAs. This means you will need to add the addresses (these are pointers) to the image base in order to properly parse the data. Name is an RVA that points to the imported module name, such as kernel32.dll. It is null terminated. Remember that we are working with an array of import descriptors? How can we tell how many import descriptors that is in this array? The array ends with a null IMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR, so an easy way to loop through each entry is this:

TimeDateStamp can be either the proper time/date or one of the following values:

ForwarderChain is only used when supporting DLL Forward Referencing, which allows calls across DLLs to be forwarded to other DLLs. For example, some calls in Windows kernel32.dll are forwarded to other DLLs. FirstThunk points to the IAT, OriginalFirstThunk points to an array of structures representing all imported functions. This is the Import Name Table (INT). Both of these members are RVAs. Thunk? right, Im sure you know another structure is coming up. Lets take a look:

OriginalFirstThunk are RVAs that point to an array of IMAGE_THUNK_DATA structures. Ugh, yey, another structure. This one is a small one though:

Thats all there is to it. The first paramater can be 0, but it just hints the loader what ordinal number the function might be using. Name is an array of characters representing the name of the function. Heres the deal: The IAT is just a list of addresses representing functions. What functions? The functions within this IMAGE_THUNK_DATA array. Look back at that IMAGE_THUNK_DATA structure and notice that its just an union representing a function name. This is the Import Name Table (INT). For example, lets say we want to get the current address of the function thats in IMAGE_THUNK_DATA[3]. Its address will be the 3rd dword in the IAT, which can be read using IMAGE_IMPORT_DESCRIPTOR->FirstThunk. So, lets try to obtain the function name and address:

Image binding This is where things get interesting. The IAT can be filled with the addresses of the imported functions either during runtime or building time. A bounded image is an image that has its IAT bounded to the functions during build time. An unbounded image is an image whose IAT is filled in by the OS loader during loading time. If the image is bounded, you can do the following to call a function in an external DLL:

If the image is not bounded, the IAT contains junk. It is then the responsbility of the OS loader to update the IAT in order for the above code to work. This can be performed by reading the export table of the loaded DLL module (calling GetProcAddress(), and overwriting the IAT entry of that import function. Overwriting the IAT can be done by following the above - when you get the functions IAT entry, just overwrite it :) This method can also be useful for installing hooks in DLLs and other modules. Supporting resourcesIntroduction Have you ever wondered how the Windows kernel can display an image and work with an XML configuation file without loading anything from disk? Have you ever worked with adding resources but wondered if it was possible to support them in an OS? The answer is a "yes, of course!" Parsing resources is a bit more complex then the other directory types, however. Like the other sections, there is a base IMAGE_RESOURCE_DIRECTORY structure that can be obtained from the DataDirectory member of the optional header:

Notice the pattern with how to access these sections? Oh, right, onto the new structure:

This structure doesnt have much of any interesting fields, except the last three. If you have worked with Win32 resources, you might know that resources can be idenitified by ID or name. Two of the members in this structure will let us know the number of these entries, and the total amount of entries (NumberOfNamedEntries + NumberOfIdEntries), which is useful in looping through all of the entries. As you can probably guess, the entries are in the DirectoryEntries array. DirectoryEntries consists of an array of IMAGE_RESOURCE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY structures, which follow the format:

Alright, this is an ugly structure. This structure represents a single resource, or resource directory.

Resource directory structure resource or resource directory? Lets stop for a moment. (*grabs a cup of coffee*) ok, it is important to know that resources are stored as a tree. This tree is structured like this:

There are a number of different resource groups which let us know the type of resources are in this group. Here are the group IDs:

First, lets look at looping through all of the entries in a resource directory:

This is simple enough, huh? The Id member of IMAGE_RESOURCE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY is used to store the group ID. If we were looking for a bitmap, it would be in the bitmap group of the root directory, so look for the entry with ID=2. Because IMAGE_RESOURCE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY represents both resource entries and directories, how can we tell what it is? Why, the DataIsDirectory member of course: If this member is set, its a directory. Ah, but if its a directory, how can you read the directory? Lets take a look:

This one isnt to bad. If the entry is a directory, the above obtains the offset to the new directory from the OffsetToDirectory and adds it to .. what? the startOfResourceSection!? Thats right... this is an offset, but not an RVA. I know ... Why Microsoft, Why!? The start of the resource section is actually the address of the first member of the IMAGE_RESOURCE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY array. So by adding this address to the offset obtained from OffsetToDirectory you can obtain the pointer to the IMAGE_RESOURCE_DIRECTORY structure for this directory. Yes, then the whole process of reading those directory entries begins :) If you are in the process of parsing the directory for your specific resource, just loop through all of the resource entries in the directory. If the resourceEntry ID field matches that of the resource ID you are trying to find (program specific ID here), then you have found the resource data. The resource data is stored in a ... zomg! structure! It can be obtained from the OffsetToData member of the directory entry structure. Simular to the OffsetToDirectory member, this too is an offset from the start of the resource section. Once you obtained the pointer, you can extract the resource data. Lets take a look at that structure:

Thats it! OffsetToData is an RVA to the real resource data, and Size is the size of that data, in bytes. For example, if we were looking for a bitmap resource, OffsetToData would be the RVA pointing to the bitmaps BITMAPINFOHEADER structure, which can be handled by any bitmap loader. ConclusionThats all for this chapter. There are some planned updates to including covering additional sections (debug data and COMDATS) as well. There is no demo for this chapter - it is primarily released for anyone that is interested in the internal workings of the PE executable file format and working with it. For the main series, we might only be loading and executing the program, so all of the other information is provided for completeness only. All code provided in text for demenstration has been tested (slightly modified) to work. In the upcoming chapters, we will be using the PE executable file format and building a loader for supporting user mode programs. After that, on to multitasking! Until next time,

~Mike |